The extent to which academics are likely to follow the media attention, money and plaudits of the Nobel committee is a question that plagues Julian Togelius, an associate professor of computer science at NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering who works on AI. “In general, scientists follow some combination of the path of least resistance and the most bang for their buck,” he says. And given the competitive nature of academia, where funding is increasingly scarce and directly linked to researchers’ job prospects, it seems likely that the combination of a cutting-edge topic that – as of this week – has the potential to win a Nobel Prize for high achievers could be too tempting to resist.

The risk is that this can inhibit innovative new thinking. “Getting more fundamental data from nature and coming up with new theories that people can understand is hard to do,” Togelius says. But this requires deep thought. Instead, it is much more productive for researchers to run AI-enabled simulations that support existing theories and incorporate existing data, creating small leaps forward in understanding rather than giant leaps. Togelius predicts that a new generation of scientists will do just that because it’s easier.

There’s also the risk that overconfident computer scientists who helped advance the field of AI will begin to see AI work being awarded Nobel Prizes in unrelated scientific fields—in this case, physics and chemistry—and decide to follow suit. them, stepping into other people’s turf. “Computer scientists have a well-deserved reputation for poking their noses into areas they know nothing about, injecting some algorithms and calling it progress, for better and/or worse,” says Togelius, who admits that before was tempted to add extensive training in another field of science and “advance” it before thinking better of it because he doesn’t know much about physics, biology, or geology.

Hassabis is an example of using AI good to advance science. He was a neuroscientist by training, earning a PhD in the subject in 2009. and credits this experience as helping to advance AI through Google DeepMind. But even he acknowledged a shift in the way the sector achieves efficiency. “Today, [AI] it has become more difficult from an engineering point of view,” he said at his Nobel Prize press conference. “Now we have a lot of techniques that we only improve algorithmically, with no more connection to the brain.”

It can also have an impact on the type of research being done – and who is doing it, their level of knowledge in the field and the incentives behind their entry into it. Instead of researchers who have dedicated their lives to a specialty, we may see more research by computer scientists disconnected from the reality of what they are looking at.

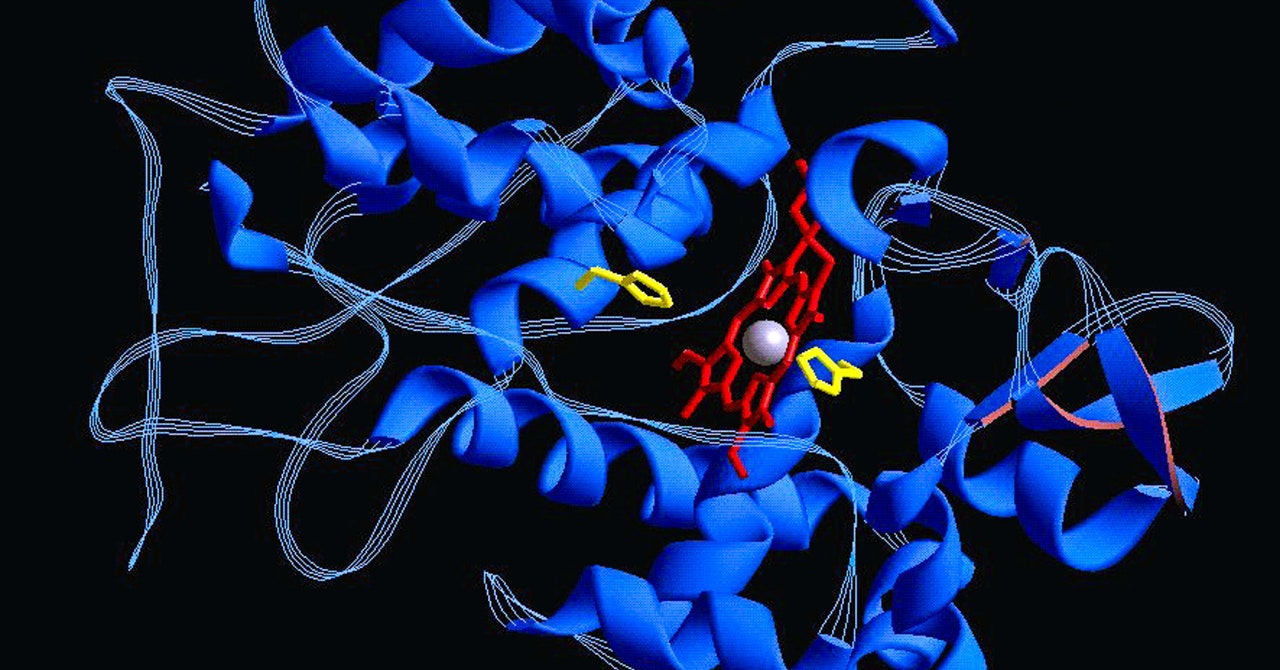

But that will likely take a back seat to the celebrations for Hassabis, Jumper and the colleagues they thanked for helping them win the Nobel Prize this week. “We are very close to cleaning up the [AlphaFold3] code to release it for free use by the academic community,” he said earlier today. “Then we’ll continue to progress from there.”